|

||||||||

Small

Bowel Resection Small

Bowel Bypass Small

Bowel Bypass Terminal

Ileectomy |

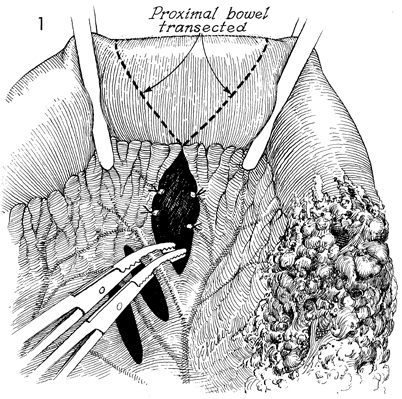

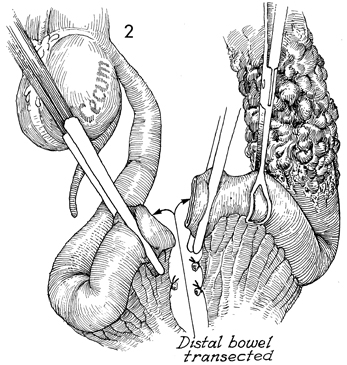

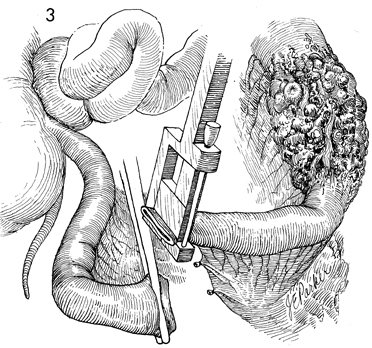

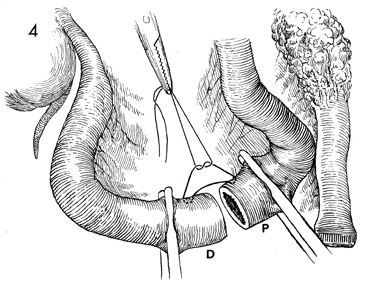

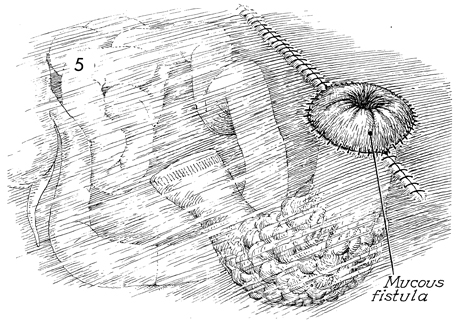

Small Bowel Bypass In those cases where the small bowel is involved with obstruction and/or fistula formation following total pelvic irradiation and/or advanced malignant disease is impacted in the true pelvis, a bypass with mucous fistula rather than a bowel resection is the operation of choice. After small bowel resection, patients frequently develop (1) recurrent small bowl obstruction from adherence of the anastomosis site to the large raw dissected areas within the true pelvis, or (2) recurrent fistula formation at the site of anastomosis, or (3) breakdown of the closure of multiple inadvertent enterotomies associated with the surgery. We have preferred bypass with end-to-end anastomosis and mucous fistula rather than the side-to-side anastomosis technique. Although the side-to-side anastomosis is more aesthetically acceptable to the patient, it is frequently associated with recurrent obstruction and persistent fistula drainage because it does not isolate the diseased portion of small bowel. The end-to-end or end-to-side technique of small bowel bypass requires a mucous fistula with an abdominal stoma that eventually contracts, produces small amounts of mucus, and has a lower incidence of recurrent obstruction and fistula drainage. Physiologic Changes. In this operation, continuity of the intestine is established, and the patient is able to regain oral alimentation. With loss of the terminal ileum, however, fat-soluble vitamins and high-molecular-weight fat absorption can be disturbed, and postoperative diarrhea is frequently encountered. These undesirable side effects can be reduced with modification of the patient's diet. Vitamins can be replaced either systemically, as for vitamin B12, or by therapeutic oral supplementation, as for vitamins A, D, E, and K, which will be absorbed by the proximal intestine. The mucous fistula may drain excessively until the pathologic indication for the bypass has been relieved. One month postoperatively, mucous drainage is usually scant, and most patients wear only a small gauze dressing over the mucous fistula stoma site. Points of Caution. We have found that the segment of bowel to be brought out as the mucous fistula stoma is optional. From a physiologic point of view it would seem that the peristaltic end of the segment should be used. If additional dissection is required to bring out the peristaltic end of the segment, however, the antiperistaltic end can be brought out as the mucous fistula stoma with equal effect. Caution should be taken to ensure the vascular integrity of the terminal ileum. The blood supply to the terminal 10 cm of ileum is unreliable. This is particularly true if the patient has received total pelvic irradiation. If there is any doubt as to the integrity of the blood supply in the terminal ileum, the ileoileal anastomosis should be abandoned, and an ileoascending colostomy should be performed. Technique

|

|||||||

Copyright - all rights reserved / Clifford R. Wheeless,

Jr., M.D. and Marcella L. Roenneburg, M.D.

All contents of this web site are copywrite protected.