Vagina

and Urethra

Anterior Repair and Kelly

Plication

Site Specific Posterior Repair

Sacrospinous

Ligament Suspension of the Vagina

Vaginal Repair of Enterocele

Vaginal Evisceration

Excision of

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Correction of

Double-Barreled Vagina

Incision

and Drainage of Pelvic Abscess via the Vaginal Route

Sacral Colpoplexy

Le Fort Operation

Vesicovaginal Fistula

Repair

Transposition

of Island Skin Flap for Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

McIndoe Vaginoplasty

for Neovagina

Rectovaginal Fistula

Repair

Reconstruction of

the Urethra

Marsupialization

of a Suburethral Diverticulum by the Spence Operation

Suburethral

Diverticulum via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Urethrovaginal

Fistula Repair via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Goebell-Stoeckel

Fascia Lata Sling Operation for Urinary Incontinence

Transection

of Goebell-Stoeckel Fascia Strap

Rectovaginal

Fistula Repair via Musset-Poitout-Noble Perineotomy

Sigmoid

Neovagina

Watkins Interposition Operation |

Vesicovaginal Fistula Repair

Vesicovaginal fistulae are usually secondary to obstetrical trauma,

pelvic surgery, advanced pelvic cancer, or radiation therapy for treatment

of pelvic cancer.

The basic principles for treatment of vesicovaginal fistulae have

changed little since the mid-19th century work of Marion Sims. The

principles are (1) to ensure that there is no cellulitis, edema, or

infection at the fistula site prior to closing the fistula and (2)

to excise avascular scar tissue and approximate the various layers

of tissue broadside to broadside without tension. A 20th century addition

to these principles is that of using transplanted blood supply from

the vestibular fat pad, bulbocavernosus muscle, gracilis muscle, or

the omentum.

The type of suture used appears less significant when the above principles

are followed. In general, we have used the glycolic acid sutures such

as Dexon or Vicryl because of their reabsorption and reduced tissue

reaction. Many surgeons prefer, however, to use a non-absorbable monofilament

suture of nylon or Prolene on the vaginal mucosa. These sutures should

not be placed into the bladder mucosa. If they are left in the bladder

for long periods of time, urinary stone formation will occur.

The purpose of the operation is to close the vesicovaginal fistula

permanently without encroaching on the ureter or the urethral orifices.

Physiologic Changes. The fistula is closed, and resumption

of micturition via the urethra resumes.

Points of Caution. Adequate blood supply to the tissue

surrounding the fistula must be provided. Excision of scar tissue is

vital to closure. Recently, tissue transplants have been used to bring

in external blood supply to the fistula site. This is a vital point

when the fistula is secondary to radiation therapy. In addition, when

the fistula is secondary to radiation therapy, we have performed a

temporary urinary diversion by ileal loop. This has dramatically improved

our ability to permanently close radiation fistulae. At a subsequent

operation, the ileal loop can be reimplanted in the dome of the bladder

after the fistula has been closed and bladder function is adequate.

In all fistulae, the principle of dual drainage is vital for proper

closure. A transurethral as well as suprapubic Foley catheter is left

in place until the fistula has closed. Generally, the transurethral

catheter is removed after 2 weeks, but the suprapubic catheter is left

in place for at least 3 weeks. Acidification of the urine with ascorbic

acid or cranberry juice is helpful in reducing urinary tract infection.

Frequent urine culture and appropriate antibiotic therapy are indicated,

however.

If an alkaline urine is present with a vesicovaginal

fistula, the urine will precipitate triple-sulfate crystals and deposit

them on the opening of the vagina.

These are quite painful and must

be completely removed prior to closure.

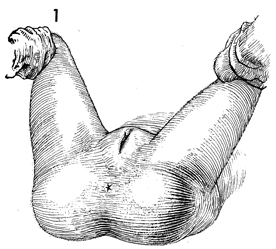

Technique

For vesicovaginal fistula closure

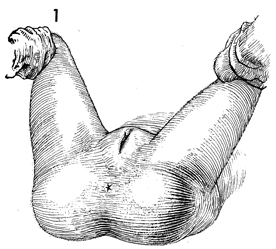

the patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. The vulva

and vagina are prepped and draped. |

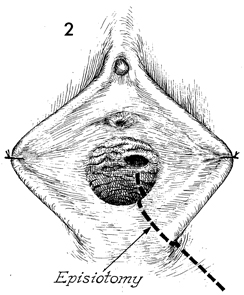

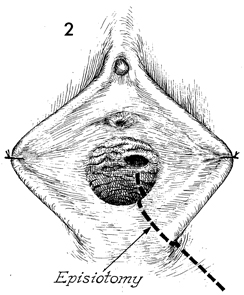

Adequate exposure of the fistula

must be made. Many unsuccessful fistula closures have resulted

from the failure to achieve adequate exposure of the fistula

site, poor placement of the sutures, and closure of the fistula

under tension. A large mediolateral episiotomy is frequently

required and should be carried up to the area of the fistula. |

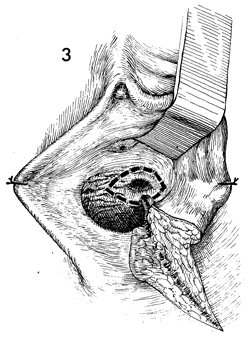

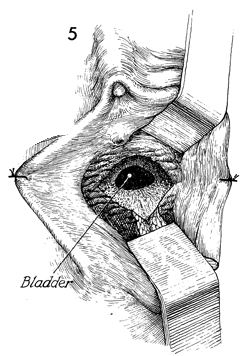

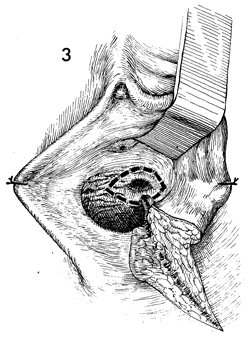

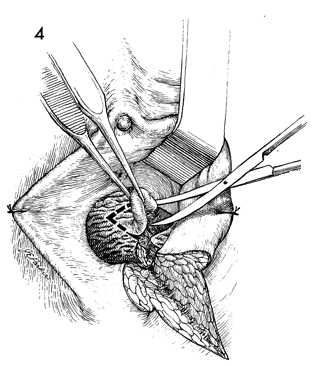

With adequate exposure the fistula

tract can be excised with a scalpel. The incision is carried

around the circumference of the fistula. |

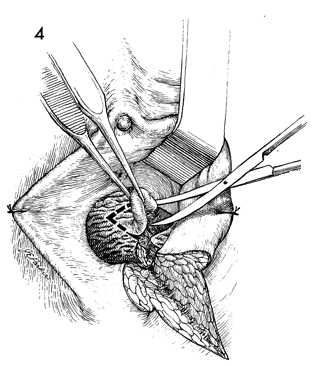

The margin of the fistula tract

is elevated with thumb forceps and excised with Metzenbaum scissors.

The entire tract is dissected. Frequently, when dense scar tissue

has been released, the fistula will be 2-3 time larger than noted

preoperatively. |

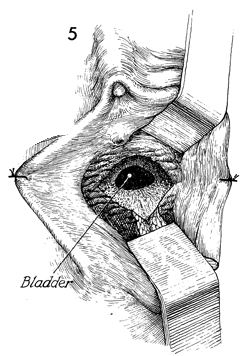

The layers of the bladder wall and

vagina should be adequately delineated, and each of these layers

should be mobilized to allow the layers to be drawn together

with fine sutures without tension. |

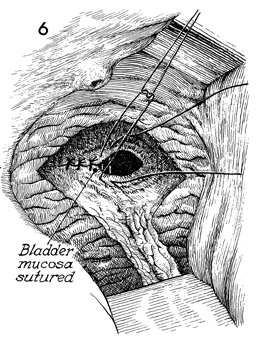

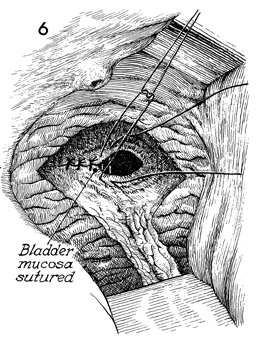

The bladder mucosa is identified and

closed with interrupted 4-0 synthetic absorbable suture. An attempt

should be made to keep the suture in the submucosal layer. We do

not perform running locking sutures or continuous suture, since

we feel this reduces the blood supply that is vital to proper closure. |

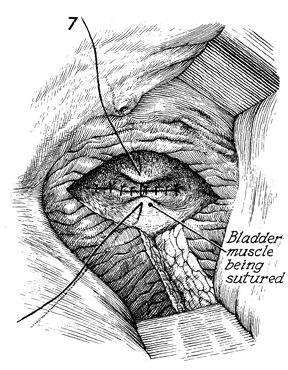

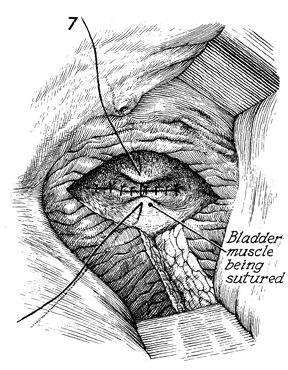

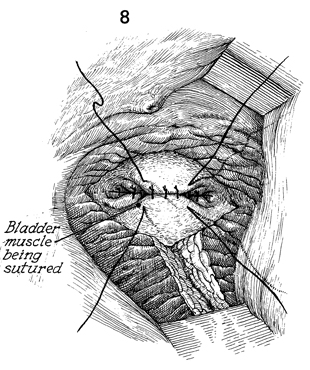

A second layer, the bladder

muscle, is closed with 2-0 synthetic absorbable suture. |

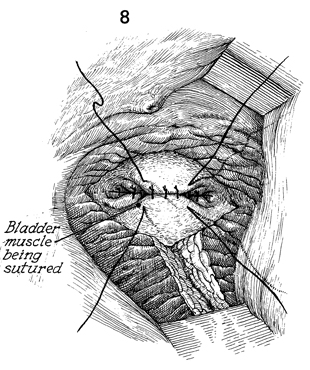

The bladder muscle is completely closed

over the fistula area with interrupted 2-0 synthetic absorbable

suture. |

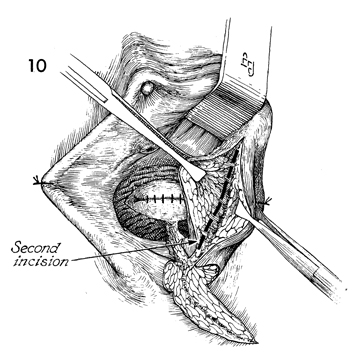

At this point, it is necessary

in high-risk cases to seek an external blood supply for the

fistula site. This can be the bulbocavernosus muscle from beneath

the labia majora, or in cases where a large fistula exists

or where the fistula is high in the vaginal canal, the gracilis

muscle from the leg or the rectus abdominis muscle can be brought

in to cover the fistula site.

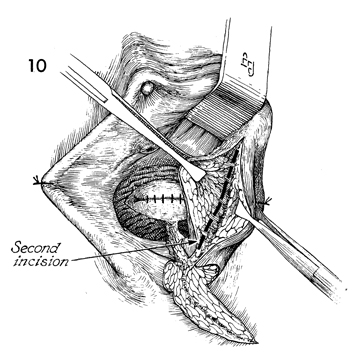

If the bulbocavernosus is

selected, two incision sites are acceptable. One is on the

inside of the labia minora as seen in Figure 9. The other is

down the body of the labia majora. If the latter incision is

selected, the bulbocavernosus muscle must be tunneled under

the labia minora into the episiotomy wound. |

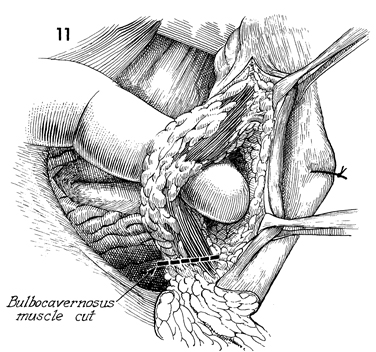

Allis clamps are used for retraction

of the labia, and a scalpel is used for dissection down to the

bulbocavernosus muscle. It is important to enlarge the incision

so that the entire muscle can be visualized. |

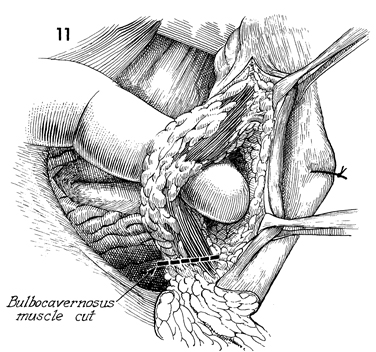

The bulbocavernosus muscle is identified

and mobilized. Frequently, at the level indicated here, the

branches of the pudendal artery and vein enter the muscle and

may have to be clamped and ligated for hemostasis. The bulbocavernosus

muscle should be mobilized by blunt and sharp dissection up

to the level of the clitoris and transected at its insertion

in the perineal body. |

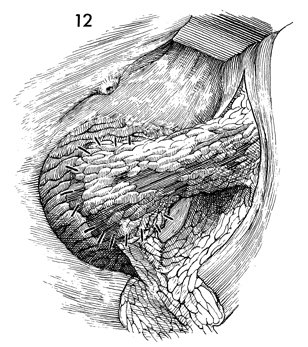

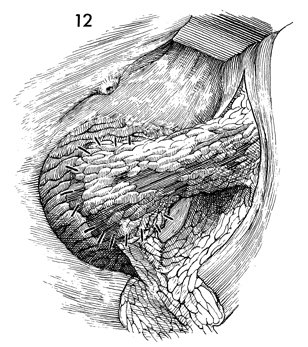

If the initial incision has been made

on the inside of the labia minora, no tunneling of the bulbocavernosus

muscle is needed, and the muscle is swung into position, covering

the fistula site. It is sutured to the perivesical tissue with

interrupted 3-0 synthetic absorbable sutures. If the initial incision

has been carried over the labia majora, a tunnel is created with

a Kelly clamp under the labia minora into the episiotomy incision.

The bulbocavernosus muscle is pulled through this tunnel, applied

to the fistula site, and sutured into place with interrupted 3-0

synthetic absorbable suture. |

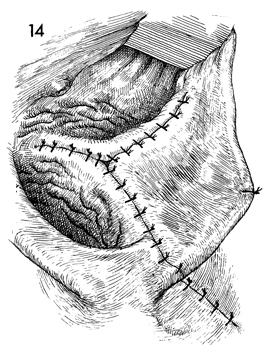

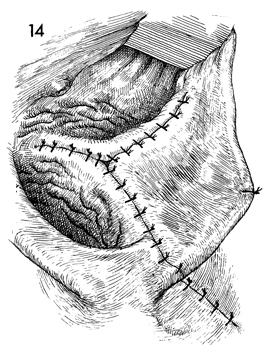

The vaginal mucosa must be mobilized

for closure without tension. Generally, the wound is closed with

interrupted 0 synthetic absorbable suture. |

The vaginal incision, the episiotomy

incision, and the incision for the bulbocavernosus muscle transplant

are closed. |

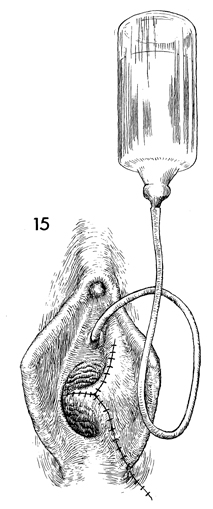

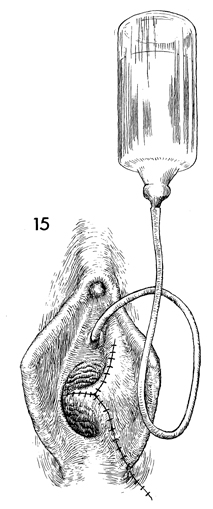

A Foley catheter is inserted

through the urethra. The bladder is generally filled with approximately

200 mL of methylene blue or sterile milk solution to ascertain

if the fistula is completely closed. We frequently perform this

same procedure after Steps 7 and 8 to demonstrate complete closure

of the fistula site.

In addition to the transurethral

Foley catheter, a suprapubic Foley catheter is placed as demonstrated

in Bladder and Ureter. Dual drainage for the fistula closure is vital. |

|

|