Vagina

and Urethra

Anterior Repair and Kelly

Plication

Site Specific Posterior Repair

Sacrospinous

Ligament Suspension of the Vagina

Vaginal Repair of Enterocele

Vaginal Evisceration

Excision of

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Correction of

Double-Barreled Vagina

Incision

and Drainage of Pelvic Abscess via the Vaginal Route

Sacral Colpoplexy

Le Fort Operation

Vesicovaginal Fistula

Repair

Transposition

of Island Skin Flap for Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

McIndoe Vaginoplasty

for Neovagina

Rectovaginal Fistula

Repair

Reconstruction of

the Urethra

Marsupialization

of a Suburethral Diverticulum by the Spence Operation

Suburethral

Diverticulum via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Urethrovaginal

Fistula Repair via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Goebell-Stoeckel

Fascia Lata Sling Operation for Urinary Incontinence

Transection

of Goebell-Stoeckel Fascia Strap

Rectovaginal

Fistula Repair via Musset-Poitout-Noble Perineotomy

Sigmoid

Neovagina

Watkins Interposition Operation |

Vaginal Evisceration

Although vaginal evisceration of the intestine is rare and usually

follows hysterectomy within the immediate postoperative period, some

cases have been reported years after surgery. The problem can arise

after abdominal as well as vaginal hysterectomy and also as a sequela

of the rupture of large enteroceles, with or without previous hysterectomy.

A contemporary source of vaginal evisceration has been suction curettage

for termination of pregnancy. During this procedure, if the uterine

wall is perforated, the small intestine can be sucked into the eye

of the vacuum curet and pulled through the perforation in the uterus

and out into the vagina.

The etiology of vaginal evisceration, except for that associated with

suction for termination of pregnancy, is not associated with any specific

pattern of events.

Physiologic Changes. The anatomy of the small bowel

and the length of its mesentery make vaginal evisceration difficult.

If a laceration occurs in the mesentery of the small bowel, evisceration

is more likely. All patients with vaginal evisceration must undergo

an exploratory laparotomy with extensive inspection of the small bowel

and its mesentery. Because of the unique blood supply to the small

bowel, an undiagnosed laceration in its mesentery may result in necrosis.

This may explain why the overall mortality from vaginal evisceration

is as high as approximately 10%.

Points of Caution. No attempt should be made to simply

replace the bowel through the vaginal cuff and close it. All patients

should be treated with an abdominoperineal approach. The entire length

of the small bowel should be carefully inspected for areas of devascularization.

A classic repair for obliteration of the cul-de-sac

through use of the vaginal cuff, the uterosacral ligaments, and the

anterior rectal wall should be made to reduce the chance of recurrence.

Technique

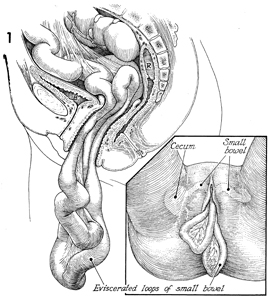

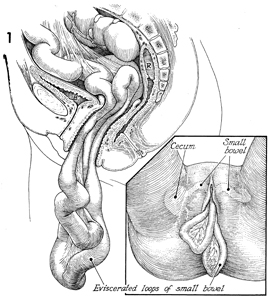

A sagittal view of the evisceration is

shown. In this particular case, the evisceration has occurred

through an open vaginal cuff after a hysterectomy. B identifies

the bladder; and R, the rectum. The insert to

Figure 1 shows the perineal view with the anatomical location

of the cecum and other loops of small bowel.

|

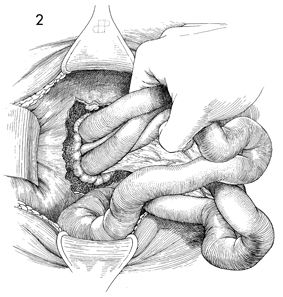

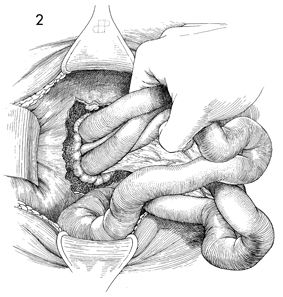

An exploratory laparotomy has

been performed, and the loops of the eviscerated small bowel

are carefully withdrawn into the peritoneal cavity.

|

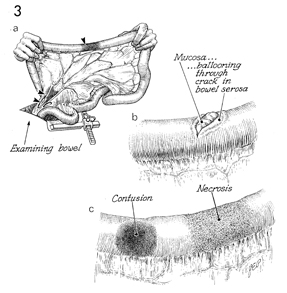

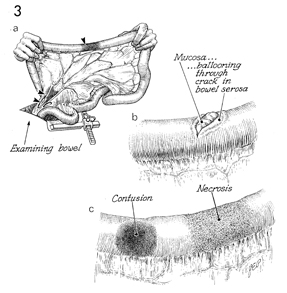

The entire small bowel is carefully

inspected from the ileocecal junction to the ligament of Treitz.

In a are areas

of devascularization and laceration in the mesentery that cause

acute loss of blood to the small bowel. In b,

a potential enterotomy with laceration of the serosa and muscularis

is causing the intestinal mucosa to balloon through a crack in

the bowel serosa. Contusions and necrosis are depicted in c. |

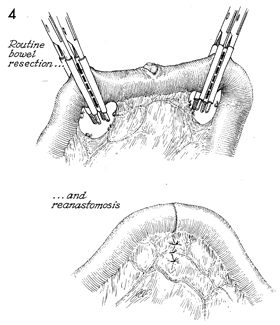

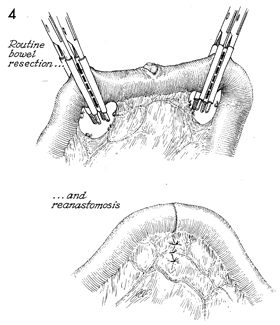

It is wise for the surgeon to resect

all areas of contusion, necrosis, and enterotomy and to carefully

inspect the vasculature in the small bowel mesentery. Linen-shod

clamps are placed in an oblique fashion away from the defect

to ensure that the antimesenteric border of the small bowel used

in the anastomosis will have an excellent blood supply.

The anastomosis is performed according

to the Gambee or stapler technique as indicated in the section

Small Bowel. The insert shows

the mesentery plicated with interrupted absorbable suture. |

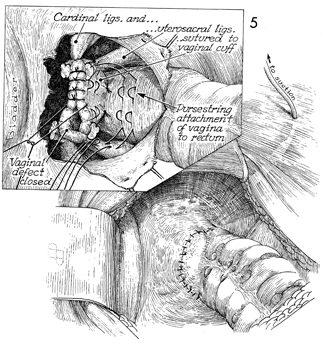

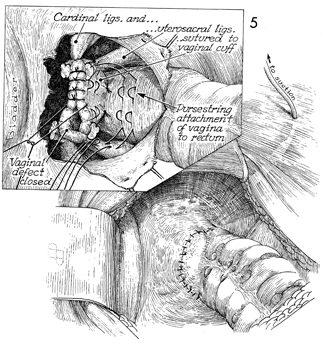

The opening in the vagina through which

the evisceration occurred is shown. After the small bowel has

been adequately inspected and cared for, the defect in the

pelvis must be repaired. The important structures shown here

are the cardinal ligaments, uetrosacral ligaments, anterior

rectum, and vagina. The cardinal ligaments should be reapproximated

to the angles of the vagina. The vaginal defect itself should

be closed with 0 synthetic absorbable suture.

The cul-de-sac should be obliterated

by several 0 synthetic absorbable sutures placed in the posterior

vaginal wall through the uetrosacral ligaments, the anterior

wall of the rectum, the uetrosacral ligament on the opposite

side, and back to the posterior vaginal wall. After all of these

sutures have been placed, they should be progressively tied from

the deepest to the most superficial.

The pelvic peritoneum should

be reconstructed. If there has been any contamination from intestinal

contents, a suction drain should be placed in the pelvis.

|

|

|