Vagina

and Urethra

Anterior Repair and Kelly

Plication

Site Specific Posterior Repair

Sacrospinous

Ligament Suspension of the Vagina

Vaginal Repair of Enterocele

Vaginal Evisceration

Excision of

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Correction of

Double-Barreled Vagina

Incision

and Drainage of Pelvic Abscess via the Vaginal Route

Sacral Colpoplexy

Le Fort Operation

Vesicovaginal Fistula

Repair

Transposition

of Island Skin Flap for Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

McIndoe Vaginoplasty

for Neovagina

Rectovaginal Fistula

Repair

Reconstruction of

the Urethra

Marsupialization

of a Suburethral Diverticulum by the Spence Operation

Suburethral

Diverticulum via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Urethrovaginal

Fistula Repair via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Goebell-Stoeckel

Fascia Lata Sling Operation for Urinary Incontinence

Transection

of Goebell-Stoeckel Fascia Strap

Rectovaginal

Fistula Repair via Musset-Poitout-Noble Perineotomy

Sigmoid

Neovagina

Watkins Interposition Operation |

Rectovaginal Fistula Repair

Rectovaginal fistulae must be divided into two groups.

The first group consists of those that occur secondary to obstetric

or gynecologic surgery for benign disease. The second group consists

of those that are associated with radiation therapy for pelvic malignancy.

Rarely is a diverting colostomy needed for fistulae from benign disease.

A transverse colostomy is always needed, however, for pelvic cancer

patients who have rectovaginal fistulae secondary to irradiation. An

outside blood supply, such as a muscular flap, is not required for

the repair of small rectovaginal fistulae secondary to obstetric or

gynecologic surgery, unless there is excessive scarring or repeated

attempts at closure have been unsuccessful. Patients with rectovaginal

fistulae associated with pelvic irradiation, however, require a vascular

flap to improve blood supply to the irradiated tissues.

The bulbocavernosus

muscle is the most convenient source of blood supply, but other sources

include the omentum, gracilis muscle, and myocutaneous flaps.

The cardinal

principles of repair of rectovaginal fistulae are (1) delay of repair

until all inflammation has cleared at the fistulae site, even if a

preoperative perineotomy is required; (2) excision of all fibrotic

and scar tissue surrounding the fistulous tract; (3) complete mobility

of the rectum and colon to eliminate any tension on the rectal mucosa

after excision of the scarred tissue; (4) use of delicate surgical

technique to preserve as much vascularity as possible; (5) broad surface-to-surface

closure; (6) improved vascularity using an outside blood supply; and

(7) diverting colostomy, in cases of irradiation, until 3-4 months

after the fistula has been confirmed closed by repeated examination.

Physiologic Changes. The rectovaginal

fistula is closed, and normal defecation per anus is resumed.

The bulbocavernosus

flap used to cover the rectovaginal fistula suture line improves vascularity

and gives an additional layer to the closure, thus improving the chances

of permanent fistula repair.

Points of Caution. The margins of

the rectal mucosa must lie adjacent to each other without tension.

Tension on the rectal mucosa suture line will invariable result in

separation of the wound. Hemostasis is a vital factor. The hemorrhoidal

plexus of veins can be difficult to control, but meticulous technique

in clamping, tying, and/or electrocoagulating each of these vessels

is imperative to fistula closure.

Dilatation of the anus at operation

produces temporary rectal paralysis of the sphincter muscle and, thereby,

temporary rectal incontinence, preventing the buildup of flatus and

stool in the terminal rectum and avoiding tension on the suture line.

Technique

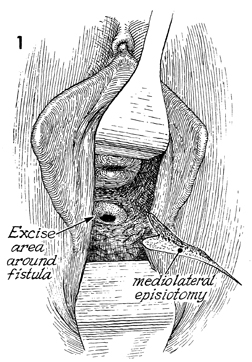

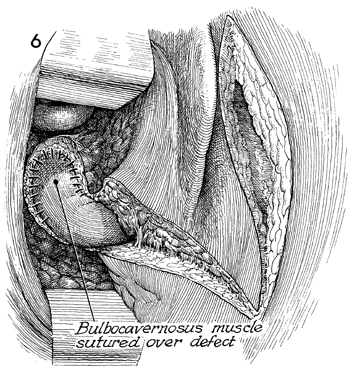

Occasionally, a fistula high inside

a narrow vagina is difficult to expose. Therefore, a mediolateral

episiotomy should be performed without hesitation to allow maximum

exposure to the operating site. The mediolateral episiotomy should

be extended up the vaginal mucosa to the margin of the fistula.

If adequate exposure cannot be obtained completely from the vaginal

approach, the abdominal route should be considered, particularly

in those cases where the fistula is high in a deep vagina. |

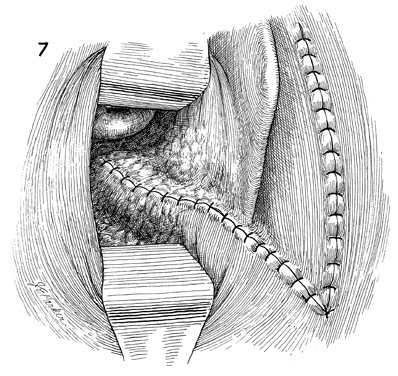

Extreme care should be taken that

the bowel mucosa is adequately mobilized and that devitalized,

scarred, or avascular portions of the mucosa have been excised.

If the intestinal mucosa cannot be mobilized and it is apparent

that the closure of the intestinal mucosa will be under tension,

the surgeon should perform a laparotomy and totally mobilize

the rectosigmoid colon from above. Many fistula repairs fail

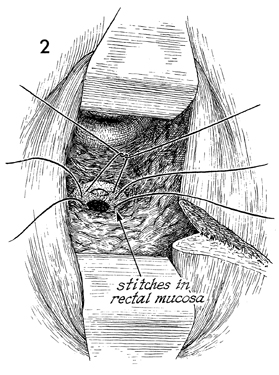

because this in not done. After adequate mobilization of the

intestinal mucosa, the edges of the intestinal mucosa are closed

in an inverting fashion with interrupted 3-0 Dexon suture with

a Lembert stitch. |

The perirectal fascia and even some

levator ani muscle may be drawn into a second layer of closure

using 0 Dexon. |

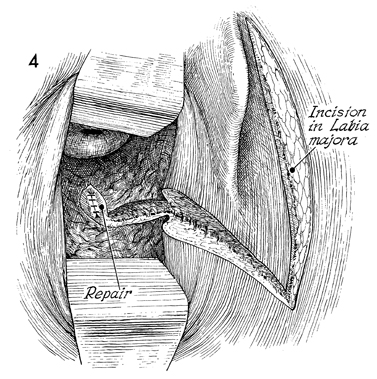

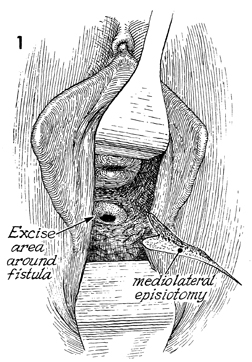

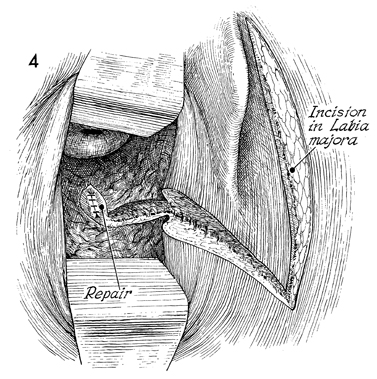

If an outside blood supply is desirable,

the margin of the excised fistula tract is connected with the

incision of the episiotomy. The bulbocavernosus muscle is palpated

under the labia majora, and a longitudinal incision is made down

the labia majora through the fat pad until the bulbocavernosus

muscle is located. |

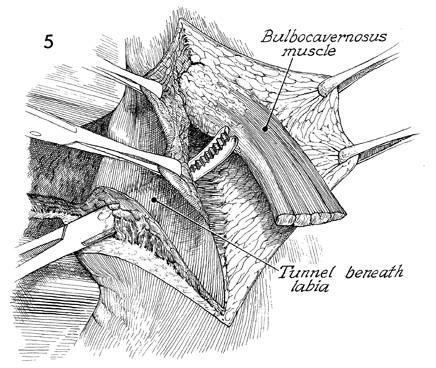

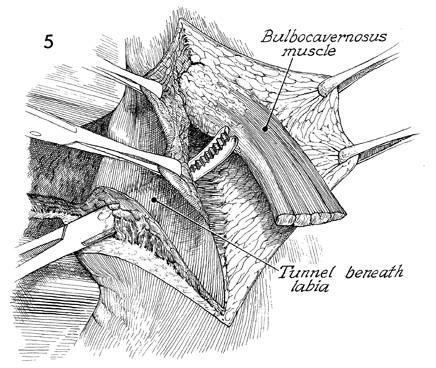

The bulbocavernosus muscle is dissected

out and transected above its insertion into the perineal body,

leaving its blood supply from the branches of the pudendal artery

intact. A tunnel approximately 3 cm wide is created from inside

the vaginal canal with a Kelly clamp, and the bulbocavernosus

muscle is drawn through this tunnel underneath the labia minora

and hymenal ring. |

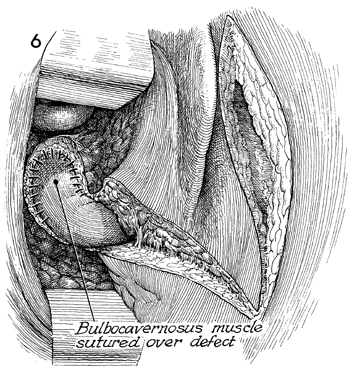

The bulbocavernosus muscle is sutured

over the perirectal fascia with interrupted 3-0 Dexon sutures. |

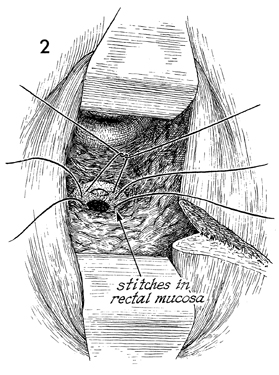

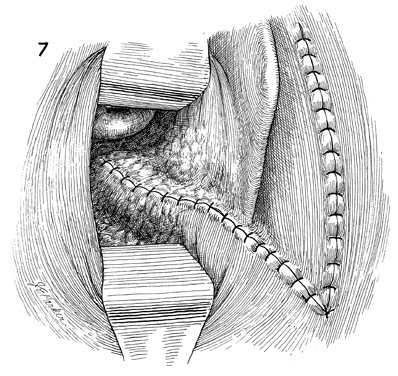

The edges of the vaginal mucosa

are then approximated with interrupted 2-0 Dexon sutures. The

wound over the labia minora may be sutured by subcuticular 3-0

Dexon or interrupted 4-0 nylon sutures. Occasionally, there will

be troublesome bleeding from the bed of the bulbocavernosus muscle.

If this cannot be brought under adequate control by delicate

clamping and suturing, it is often possible to pack this area

with Avitene collagen hemostat. In this event, a small 1/4-inch

closed suction drain can be brought out from the inferior edge

of the labial incision. To have the entire wound completely dry

and avoid hemostatic agents or drains is preferred, however.

Care must be taken to ensure

that the stool is completely soft and that there is no buildup

of flatus above the sphincter. The latter can be accomplished

by two techniques. One is to dilate the sphincter to 4-5 cm manually,

thus temporarily paralyzing the rectal sphincter and leaving

the patient fecally incontinent for approximately 1 week. The

other is to incise the rectal sphincter at the 7 or 9 o'clock

position in one plane only. Multiple radial incisions in the

rectal sphincter may produce permanent fecal incontinence. It

is highly recommended that the patient use a stool softener for

3-6 months following fistula repair.

|

|

|