Vagina

and Urethra

Anterior Repair and Kelly

Plication

Site Specific Posterior Repair

Sacrospinous

Ligament Suspension of the Vagina

Vaginal Repair of Enterocele

Vaginal Evisceration

Excision of

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Correction of

Double-Barreled Vagina

Incision

and Drainage of Pelvic Abscess via the Vaginal Route

Sacral Colpoplexy

Le Fort Operation

Vesicovaginal Fistula

Repair

Transposition

of Island Skin Flap for Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

McIndoe Vaginoplasty

for Neovagina

Rectovaginal Fistula

Repair

Reconstruction of

the Urethra

Marsupialization

of a Suburethral Diverticulum by the Spence Operation

Suburethral

Diverticulum via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Urethrovaginal

Fistula Repair via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Goebell-Stoeckel

Fascia Lata Sling Operation for Urinary Incontinence

Transection

of Goebell-Stoeckel Fascia Strap

Rectovaginal

Fistula Repair via Musset-Poitout-Noble Perineotomy

Sigmoid

Neovagina

Watkins Interposition Operation |

Sacral Colpopexy

Sacral colpopexy is a surgical procedure designed

for correction of prolapse of the vagina. It is an ideal procedure

for those women who are sexually active but who have total prolapse

of the vaginal canal. Prolapse of the vagina can occur following

a hysterectomy or with the uterus in place. If the uterus is still

in place and the patient is menopausal, it is best to remove it by

a hysterectomy (Uterus) prior to performing sacral colpopexy, unless

there are compelling reasons to leave it in situ. Sacral colpopexy

is an alternative procedure to sacrospinous ligament suspension of

the vagina (see Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension of the Vagina). In

some clinics, sacral colpopexy is reserved for those patients who have

recurrent prolapse following sacrospinous ligament suspension of the

vagina, since sacral colpopexy involves a pelvic laparotomy, whereas

the sacrospinous ligament suspension of the vagina can be performed

through the vagina. To date, there are no prospective, randomized studies

showing that one procedure is more efficacious than the other. Both

procedures have their advocates.

The strap material used in the sacral colpopexy varies.

There are some who prefer synthetic permanent mesh material made from

Prolene (Marlex and Mersilene). We prefer the patient's own fascia.

Our preference for the patient's own fascia (rectus fascia or fascia

lata) stems from our desire to avoid the sequelae of putting a foreign

body into or around the bacteria-contaminated vagina. The additional

effort to obtain fascia lata or rectus fascia is small compared to

the long-term sequelae of an infected foreign body.

Physiologic Changes. Vaginal

prolapse is an incapacitating and debilitating problem for women.

The exposed vaginal mucosa can become ulcerated with associated bleeding

and infections.

Replacing the vagina back into the pelvis in its proper anatomical

configuration is important. The normal vagina is shaped somewhat like

a backward hockey stick. The upper one-half to one-third of the vagina

should tilt posteriorly back upon the rectum. If the surgeon creates

a situation for the apex of the vagina to be in the midplane of the

pelvis, intra-abdominal pressure will produce recurrent prolapse.

Points of Caution. Sacral colpopexy is not a difficult

operation to perform. Several points need to be emphasized, however,

if the procedure is to be done successfully.

First, after entering the abdomen, identification of the right ureter

is vital. It should be mobilized and retracted laterally. The rectosigmoid

colon should also be mobilized and retracted laterally.

The vascular plexus on the periosteum of the sacrum can be associated

with copious bleeding if it is not properly managed.

The material used for the strap (natural fascia or

synthetic mesh) should be of the proper length and width to support

the apex of the vagina. The strap must be retroperitonealized and not

cross the pelvis like a "clothesline." Such a situation is an invitation

to internal herniation and incarceration of the small bowel, leading

to obstruction and necrosis.

Technique

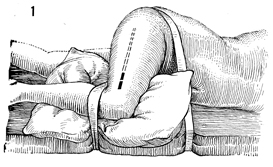

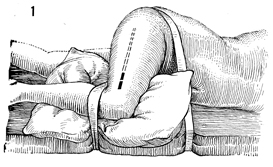

For the surgeon to harvest the fascia

lata, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position

with flexion of both the hips and knees at approximately 60°.

A pillow should be placed between the knees to abduct the thigh

until it is level. Two large pieces of tape are used to stabilize

the patient and prevent her from moving to either side. The lateral

thigh is prepped and draped. The solid line marks the

site of the initial incision, and the dotted line marks

the direction of the tunneled Masson fascia stripper. |

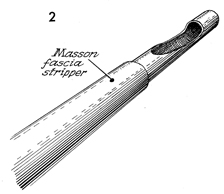

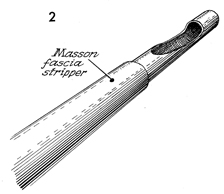

The Masson fascia stripper consists

of two hollow metal tubes-one inside, one outside. The inner

tube has a narrow opening, "the eye," near one end; the edge

of the outer tube is sharpened to allow cutting of the fascia

strip at the desired level. |

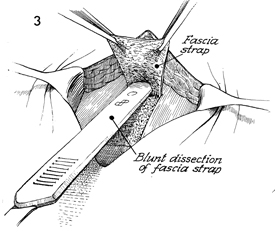

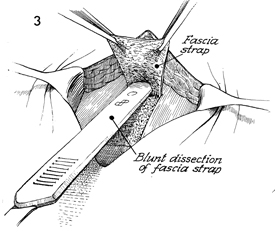

The incision is open; the base of

the fascia strap is started by hand with a scalpel. The handle

of the scalpel is used to perform blunt dissection of the fascia

strap off its bed. The finger is used to tunnel underneath the

subcutaneous fat on top of the fascia. The base of the strap

should be 4 cm wide. At least 6 cm of the strap should be taken

by the knife before applying the Masson stripper. |

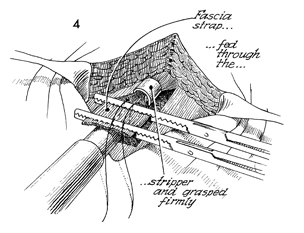

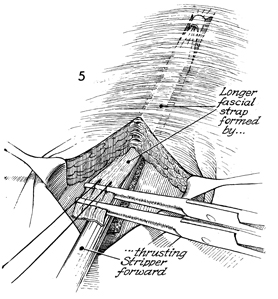

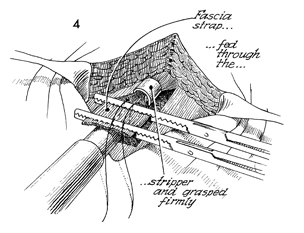

The Masson fascia stripper is moved

into position. The strap that has been formed by sharp dissection

is placed through the opening of the fascia stripper. Two straight

Kocher clamps are placed across the strap, and a suture is placed

adjacent to the Kocher clamps as a safety suture to retrieve

the strap if it breaks and retracts up the thigh. |

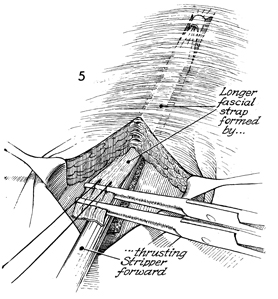

The surgeon retracts the Kocher

clamps caudally as the Masson fascia stripper is advanced cephalad.

A point is reached where the Masson fascia stripper will advance

no farther. At that point, the surgeon unscrews the handle of

the Masson fascia stripper and evulses the strap. The strap is

brought out through the leg wound. |

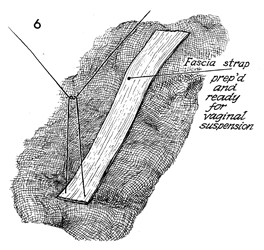

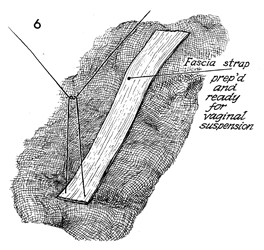

The fascia strap is shown. The suture

at the end of the strap is removed. |

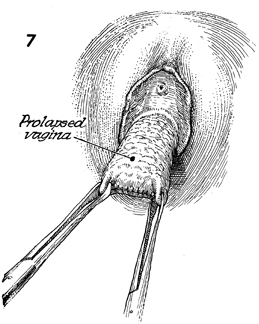

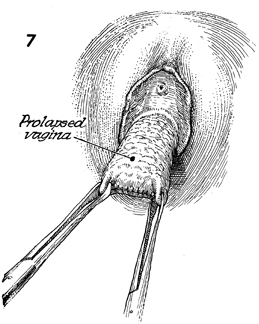

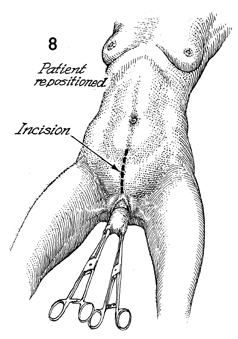

The patient is changed to the dorsal

lithotomy position. The prolapsed vagina is noted. Two Allis clamps

are placed on the vaginal apex. If a hysterectomy has previously

been performed, the suture line will be noted in the vaginal apex. |

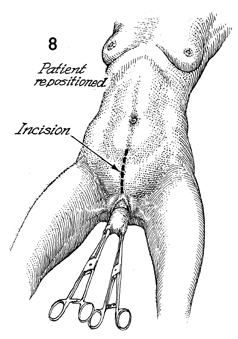

A midline incision-Pfannenstiel or midline-is

made. The peritoneal cavity is entered. |

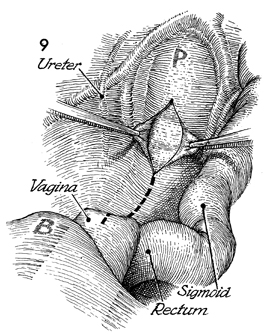

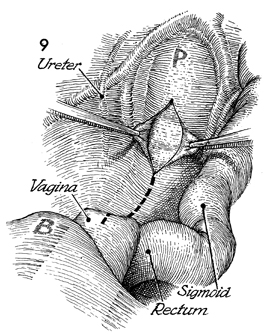

After packing the bowel away with moist gauze,

the surgeon identifies the right ureter and the rectosigmoid

colon. An incision is made in the posterior peritoneum from the

sacral promontory (P). This incision is carried down

over the cul-de-sac and the vaginal apex. The vagina is replaced

into the abdominal cavity by either a 4-cm obturator or a sponge

stick held in an ovum forceps. |

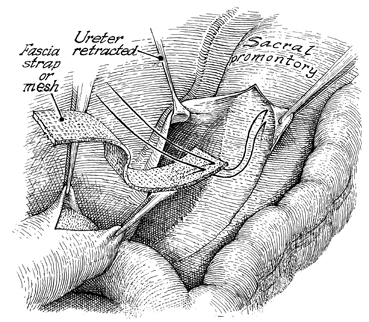

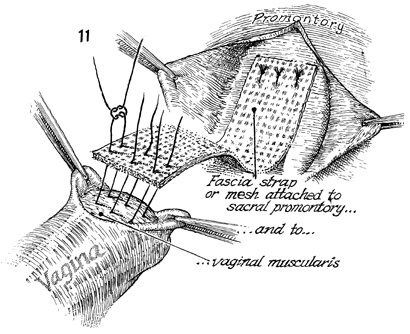

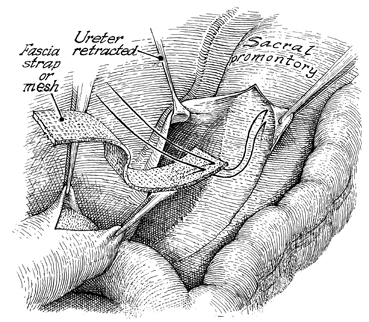

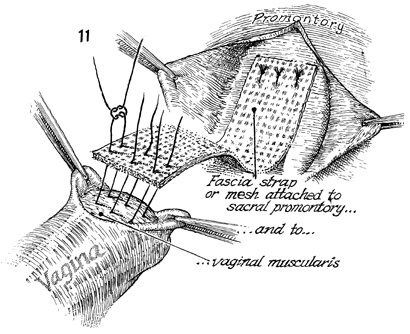

The fascia strap is sutured

to the periosteum of the sacrum. Sutures should be placed into

the periosteum of the sacrum and then brought through the fascia

as shown here. Three to four sutures are placed. The distal

end of the strap is sutured to the apex of the vagina. Three

sutures are placed in the anterior vaginal wall with interrupted

synthetic permanent sutures. The strap is placed over the dome

of the vagina, and additional sutures are applied if needed.

The cul-de-sac is obliterated by suturing the uterosacral ligaments

in the midline. |

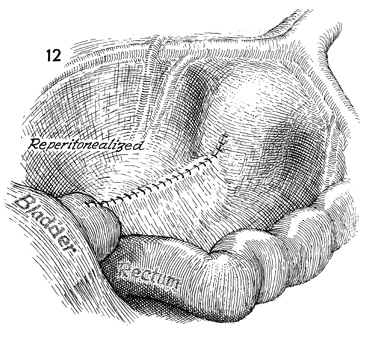

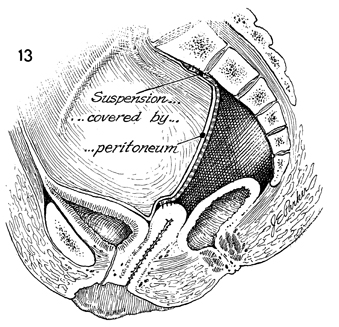

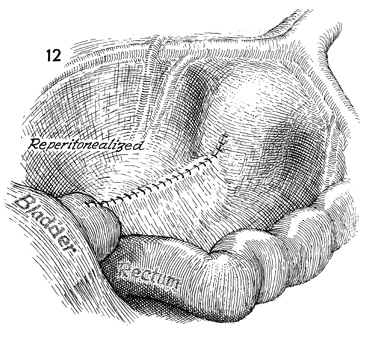

The peritoneum is sutured over

the strap to reperitonealize the pelvis and prevent the "clothesline"

effect. |

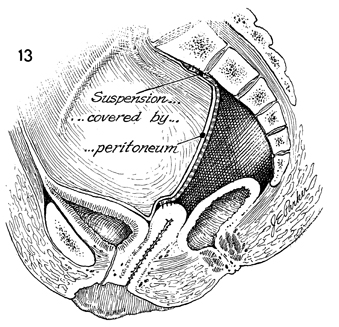

A sagittal view shows the suspension covered

by the peritoneum. The strap is sutured to the periosteum of

the sacrum and ultimately over the dome of the vaginal apex.

The vagina should lie posteriorly over the rectosigmoid colon. |

|