|

||||

Malignant

Disease: Staging

of Gynecologic Application

of Vaginal Application

of Uterine Afterloading Applicators Abdominal

Injection of Chromic Phosphate Radical

Vulvectomy Reconstruction

of the Transverse

Rectus Colonic

"J" Pouch Rectal Ileocolic Continent Urostomy (Miami Pouch) Construction

of Neoanus Skin-Stretching

System Versus Skin Grafting Gastric

Pelvic Flap for Control

of Hemorrhage in Gynecologic Surgery Repair

of the Punctured Ligation

of a Lacerated Hemorrhage

Control in Presacral

Space What

Not to Do in Case of Pelvic Hemorrhage Packing

for Hemorrhage Control

of Hemorrhage

|

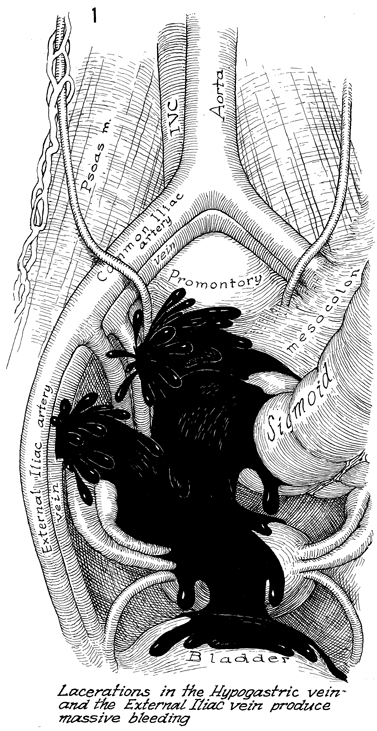

Packing for Hemorrhage Control Packing has made a popular return to trauma and pelvic surgery, based

on objective data. Every operative team should have its basic rules

concerning packing. Basically, when a hemorrhage has occurred and cannot

be controlled with the techniques mentioned in this section of the Atlas and

more than 10 units of blood have been administered, the patient will

start developing the signs and symptoms of hypovolemic shock. They

will be hypothermia and/or acidosis. The patient will also develop

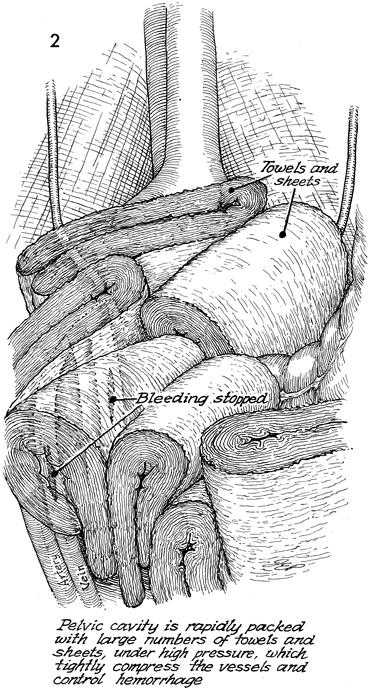

dilutional coagulopathy with bleeding from other sites. At this point, further attempts at vascular control are usually fruitless,

and it is efficacious to pack this area of the body with any large

sterile pack available. Extensive use of large packs is required; there

is no role for 4 X 4 sponges. Laparotomy packs may include tools, sheets,

and other aids to pack off this area in a proper manner. In closing the patient's abdomen the rectus fascia

should not be closed. The skin should be closed with towel clips. The

patient should be taken to the surgical intensive care unit. She should

remain intubated and on a mechanical respirator. Central venous access

must be made, and corrections must be started for all the signs and

symptoms of hypovolemic shock. The fascia should not be closed to prevent compartmental syndrome.

The large amount of packing necessary to control large vessels in the

pelvis can make ventilation extremely difficult, resulting in compartmental

syndrome. Forty-eight hours later, when all vital signs, electrolytes, hemoglobin,

prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) levels

have been corrected, the patient can be brought to the operating room,

the skin clamps and the packing can be carefully removed, and the surgeon

may frequently find little if any hemorrhage. If there is hemorrhage,

it can be properly controlled at this time with adequate operative

personnel and instruments. Technique

|

|||

Copyright - all rights reserved / Clifford R. Wheeless,

Jr., M.D. and Marcella L. Roenneburg, M.D.

All contents of this web site are copywrite protected.